The clock is ticking for trucking manufacturers to meet challenging new emissions requirements in 2024 and 2027.

On those two horizons are reductions of NOx by up to 90 percent, CO2 by up to 25 to 30 percent plus new low load cycle and in-use specifications, as Eaton makes clear in a video on diesel cylinder deactivation (CDA). This emerging technology holds real promise in reducing emissions while improving fuel economy, but it’s the emissions battle that’s really taken center stage and driven the formation of various partnerships.

Eaton has worked with Cummins to test CDA in a Cummins Efficiency Series X15 engine. Cummins has also worked with Jacobs Vehicle Systems and Tula on cylinder deactivation. They all have the same goal of getting diesel engines up to the job of meeting new low-load requirements, like when the engine’s at idle or running at low RPMs. By shutting down half of the cylinders and decreasing air flow, CDA leads to increased exhaust temperatures in the remaining cylinders which in turn cranks up temperatures during the selective catalytic reduction (SCR) process. More heat equals fewer emissions.

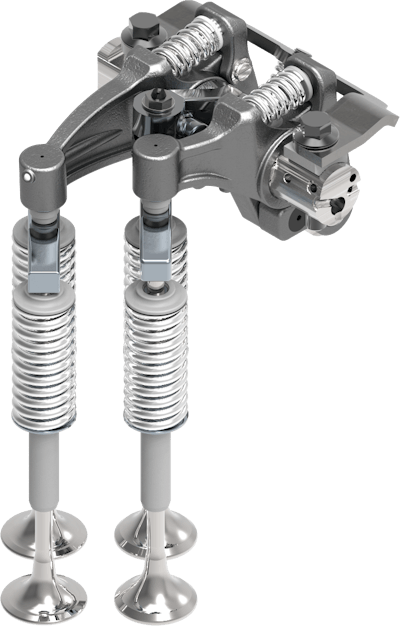

Eaton, which has produced the CDA valve train assembly shown above, reports the ideal temperature in conventional diesel engines during SCR after treatment is between 250 and 400 degrees Celsius (482 and 752 degrees Fahrenheit). Engines can struggle to reach those temperatures during low-load cycles. Diesel CDA can raise SCR temperature 100 to 200 degrees Celsius (212 to 392 degrees Fahrenheit) during low-load conditions and ultimately exceed 500 degrees Celsius (932 degrees Fahrenheit) which drastically reduces NOx, CO2 and de-sulphates the SCR.

“The inclusion of a low-load cycle and being able to do better in that low power operation is really a challenge and that’s where cylinder deactivation is one of the key technologies that we’re evaluating for future regulations because it has the ability to not only increase those temperatures but improve fuel economy while you’re doing it,” said Lisa Farrell, Cummins’ director of advanced system integration.

“Most of our traditional methods today keep the catalyst warm and burn a lot more fuel. So with CO2 regulations and climate change goals, certainly that’s not the way we want to go for meeting future NOx regulations,” Farrell continued.

"Work done by SWRI (Southwest Research Institute) on a Cummins 15L engine demonstrated that using a close-couple, dual-dosing SCR with the Eaton CDA system, a 90% reduction of NOx is achieved (meeting CARB ultra low NOx targets) while CO2 is reduced by 1% on the FTP cycle and 5 % on a Low Load cycle, relative to today’s engine," said Fabiano Contarin, product director of engine air management at Eaton’s Vehicle Group. Eaton is testing CDA with HLA (hydraulic lash adjuster) "which requires no maintenance, while CDA with mechanical lash adjustment will follow the normal maintenance procedures as today," he said.Eaton

"Work done by SWRI (Southwest Research Institute) on a Cummins 15L engine demonstrated that using a close-couple, dual-dosing SCR with the Eaton CDA system, a 90% reduction of NOx is achieved (meeting CARB ultra low NOx targets) while CO2 is reduced by 1% on the FTP cycle and 5 % on a Low Load cycle, relative to today’s engine," said Fabiano Contarin, product director of engine air management at Eaton’s Vehicle Group. Eaton is testing CDA with HLA (hydraulic lash adjuster) "which requires no maintenance, while CDA with mechanical lash adjustment will follow the normal maintenance procedures as today," he said.Eaton

On the gasoline side, on bigger engines--V8s, for example--the fuel economy benefit can easily be 10 to 15 percent, explained John Fuerst, senior vice president of engineering at Tula.

While Tula has reported a fuel savings of 4 percent through diesel CDA, emissions reductions during low-load operation is where the real magic happens.

“We’re showing two-thirds reductions of NOx on the low-load cycle combined with an almost 4% CO2 improvement,” Fuerst said.

Though fuel savings in diesel CDA may not seem like much compared to its gasoline counterparts, it can still add up fast in a hardworking Class 8 truck.

“The cost of CDA technology can be paid back by the fuel savings in 1 year on an average Class 8 truck,” said Fabiano Contarin, product director of engine air management at Eaton’s Vehicle Group.

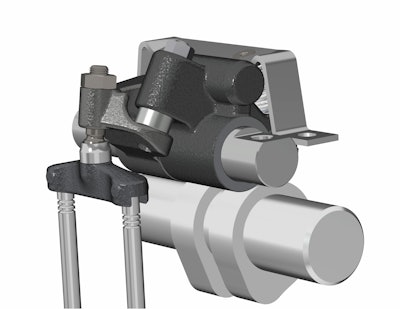

An Eaton CDA rocker arm. "Cylinder deactivation consists of deactivating the opening and closing motion of intake and exhaust valves and simultaneously turning off fuel injection to specific cylinders," Contarin said. "We do not expect an impact of CDA on oil and engine life and we do not have evidence suggesting that now. Our testing has shown that there are no adverse wear effects on deactivating cycles."Eaton

An Eaton CDA rocker arm. "Cylinder deactivation consists of deactivating the opening and closing motion of intake and exhaust valves and simultaneously turning off fuel injection to specific cylinders," Contarin said. "We do not expect an impact of CDA on oil and engine life and we do not have evidence suggesting that now. Our testing has shown that there are no adverse wear effects on deactivating cycles."Eaton

“There are still many applications where pure electric powertrains will not provide the functions needed for moving freight, either logistically or economically,” said Robb Janak, director of new technologies at Jacobs. “Therefore, we see that the diesel engine will continue to be needed for the foreseeable future. It is the goal of Jacobs and others in the commercial vehicle powertrain development space to demonstrate ways to make the diesel engine as efficient and clean as possible.”

A work in progress

Diesels have long been prized for their high energy density efficiency which far outpaces gasoline engines in terms of fuel economy. However, one of the fundamental characteristics behind those impressive fuel gains is also an Achilles heel.

“On a diesel engine, usually in light loads, you have a lot of excess air in a combustion event and that’s really great for efficiency and for transient response and being able to put fuel in quickly for diesels, but it can also be challenging because it also provides very low exhaust temperatures at lighter loads,” Farrell explained.

“By being able to essentially run the engine at a smaller displacement which is what you get when you deactivate some of the cylinders for the same amount of power you end up with a hotter exhaust and more efficient combustion in the cylinders that are operating.”

Unfortunately, there are some misunderstandings pertaining to cylinder deactivation. For instance, as Fuerst explained, CDA will not hinder power demands when needed.

“People might think, ‘I’ve got a vehicle or a truck or a car and it’s got cylinder deactivation. What am I giving up if this thing’s deactivating cylinders? How much power am I losing? And the answer is, absolutely nothing. You lose nothing. Anytime you put the pedal down you’ve got all (power) immediately. So you don’t give up any power or torque or anything else.”

"We have not experienced any change in engine oil life when operating CDA," said Robb Janak, director of new technologies at Jacobs Vehicle Systems. "The CDA mechanism uses standard engine oil to switch between CDA modes, and just like the engine brakes we design, our systems do not discernably reduce engine oil life."Jacobs Vehicle Systems

"We have not experienced any change in engine oil life when operating CDA," said Robb Janak, director of new technologies at Jacobs Vehicle Systems. "The CDA mechanism uses standard engine oil to switch between CDA modes, and just like the engine brakes we design, our systems do not discernably reduce engine oil life."Jacobs Vehicle Systems

CDA development for Class 8 truck engines is no small feat. It’s a complex system that has posed some interesting challenges along the way.

“One of the ‘perceived’ challenges in CDA application on HD engines is NVH (noise, vibration and harshness),” said Contarin. “Eaton has worked extensively on this topic and come up with a strategy of CDA actuation that limits NVH.

“In simple terms, such strategy consists of selecting the number of active cylinders in function of speed and load in order to avoid resonance, hence similar vibrations as today,” Contarin continued. “Eaton also has performed vehicle-level NVH testing and analysis, observing that when needed, the engine mounts can be optimized to achieved acceptable levels of vehicle NVH.”

Jacobs was thankfully in a position to address valve train challenges that are unique to diesel CDA systems.

“One of the challenges is that we saw that the systems developed for the passenger car market didn’t transfer well to the HD diesel engines because of their much higher valve train system loads and durability requirements,” Janak explained.

“Luckily Jacobs had already been developing a deactivation system when we created it for our High Power Density engine brake, which was specially designed for these HD engine requirements,” Janak continued. “Therefore, when there was interest in CDA for this market, we had already had over a decade of durability and vehicle testing experience.”

While Farrell said COVID constraints has slowed them down in testing their CDA-equipped X15 on the road, they’re still moving ahead with those plans and already have some exciting lab results to share at the SAE World Congress Experience which will be held online from April 13-15.