I’ve been fortunate over my career to interact with people all over the world. Based on my interactions with them, I’ve come to realize that there are some fundamental facts about American trucking that simply defy logical explanation.

I talk with my Canadian friends about why their trucks can haul upwards of 140,000 pounds, or more precisely, 63,500 kg. This configuration is a “B-Train Double”, or what we somehow have termed a “long combination vehicle” or LCV. Labels have immense influence on controlling the narrative on anything. The word “long” is relative. I can tell you that the Australians with their road trains might reasonably debate the definition of “long.” The Canadians wonder, I think quite reasonably, why they can run longer, heavier loads, even though much of the U.S. does not allow them except under special permits. It doesn’t help the explanation that states like Washington, Idaho, Oregon and Nevada run longer doubles and triples, and states like Michigan and Washington see singles running eight or more axles with heavy loads.

Some things are just hard to explain.

Then there are rest stops. Where do I start? Why is it that all one can get at a rest stop is something from a vending machine? Wouldn’t it be great if you could fill up your truck? Get a real meal at a restaurant? You just can’t do that at a U.S. rest stop. You have to go to a commercial truck stop to get amenities. The rules prohibit rest stops from competing, so all they are is a restroom, some parking, and, if you’re lucky, a working vending machine or two.

I have stopped at a lot of rest stops in my travels. I found one in Eastern Oregon that actually had a working telephone booth. I hadn’t seen a phone booth in years. Somehow having telecommunications at a rest stop was okay when the rules were made. I wonder if the rule makers realize that you can get food delivered almost anywhere now by a smart phone app. I’ve never actually seen a delivery at a rest stop, but, what an opportunity to push the regulatory envelope.

I’ve written about truck parking a few times in blogs and in the NACFE report More Regional Haul – An Opportunity for Trucking. Trucks haul more than 60% of American freight, pretty much everything in your home and office has been on a truck for at least part of its trip. During COVID-19, the population realized that trucks and truck drivers were essential. What a shock. Pre-COVID, we all apparently thought trucks and truck drivers were just topics for country music songs.

The CDC defines “essential workers” as “those who conduct a range of operations and services in industries that are essential to ensure the continuity of critical functions in the United States (U.S.).” Scan through the lengthy list and, sure enough, many transportation and logistics jobs are officially defined as “essential” to critical functions of the U.S. If trucks and truck drivers are so essential, why is it so hard for them to find a parking spot? That’s hard to explain.

Speed limits are another fun topic when talking with people overseas. Americans seem to love speed. The 1970’s oil embargo introduced Americans to the concept that going faster uses more fuel, something we were suddenly not getting enough of. The national 55 mph speed limit was enacted. Have you seen those wonderfully dated speedometers from the 1970s? Where is the top end? Not unusual for them to peg out at 100 mph. Look at today’s speedometers. Many have top ends at 140 mph or 160 mph, even on economy cars that probably would need to be towed by a Lamborghini to reach those speeds. Top speeds in the U.S. rarely exceed 75 mph to 85 mph. Yet the cars we sell are designed to go faster than that. WTF? Seriously.

The Department of Transportation studiously records and reports on annual traffic deaths, occasionally making some progress on making vehicles safer for everyone through crazy ideas like mandatory seat belts, air bags, safety glass, etc. State highway patrol officers write endless tickets for speeding. Today’s technology on everyone’s smart phones can tell exactly how fast we are going at any instant, and know what the posted speed limits are exactly where we are driving, and yet we have vehicles that can go twice as fast as that. Some states limit truck speeds slower than cars, introducing a number of challenging topics on the safety effects of differential traffic speeds and fundamental rights questions about fair and equitable regulations.

There are a lot things about speed that are hard to explain.

Hours of service is another interesting topic. You think about someone on a production line or driving a desk chair, and, turns out, there are rules limiting work days. I once sat through a presentation where an executive pointed out that China does not have these limitations and protections. Not sure if that was a veiled threat, or a reflection on how much better the U.S. cares about its workforce.

Suffice to say, there are commercial activities we seem to be almost too careful of constraining. I wonder if farmers have hours of service limitations or mandatory overtime when plowing or harvesting? Do soldiers and sailors have hours of service limitations? Truckers do, and there are a lot of opinions about that across a wide spectrum.

During emergencies, government officials can wave these requirements almost at a whim. HOS compliance has become so critical that nearly every truck driver has to electronically log their hours with mandatory equipment now installed in nearly every truck. Yet car drivers don’t have any such rules. How many social media posts have you read about someone driving 18 hours to get to a family event? How many accidents occur because of drowsy driving by operators of passenger cars?

Some things are tough to rationalize.

E-commerce is ubiquitous. I expect even in the midst of a war zone you might be able to get an overnight delivery of your favorite peanut butter. It’s truly an amazing story of how our desire for consumption, when combined with the internet and smart phones, has created an industry that can nearly instantly deliver almost anything, almost anywhere. What is hard to explain, and flies under the radar, is that all that instantaneous consumption is not necessarily consumed.

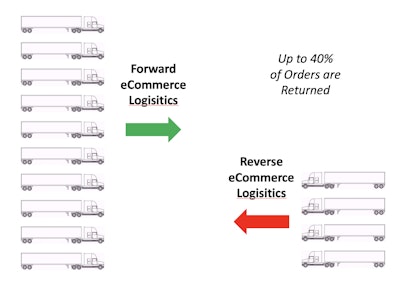

There is this thing called “reverse logistics.” Turns out that 30% to 40% or more of those nearly instantaneous deliveries wind up being sent back to vendors. Think about how much waste that inefficiency creates. Think of all the extra warehousing, all the extra truck transportation, all the energy reverse logistics requires. Shippers make no money on reverse logistics. It’s a loss, even if they somehow can put the returned products back up for sale. Put 40% in perspective — for every 10 e-commerce trucks delivering, four more are returning with what they delivered. Yet somehow we seem to focus on getting 1% better fuel economy from diesel trucks or speculating on whether or not battery electric vehicles are cost-effective solutions.

Some things just don’t make sense.

Spending for battery electric vehicles are getting a lot of discussion across the spectrum. Social media seems to have fixated on “trillions” of dollars needed to bring them about. Forget that our electrical grid was largely built years ago and is in need of updating anyway. And let's forget that we all like to breathe. Let’s just focus on that investment. What does investing $1 trillion mean to trucking?

Doesn’t that investment inherently mean a massive amount of materials will need to be moved by trucks? Doesn’t that represent new market opportunities for new business? New jobs. New customers? One International Monetary Fund estimate is that spending $1 million creates between three and seven jobs in advanced economies, perhaps as many as 30 in developing ones. A Brown University 2017 study estimated job creation by area shown in the graph here. So spending that $1 trillion might be arguing for creating jobs and increasing profitability. Yet some pro-business groups seemed focused on arguing against it. Perhaps they slept through the class that you have to spend money to make money.

Some things defy explanation.

Running freight in America is complex. Aspects may not make sense. Perhaps they are not supposed to. Maybe it’s part of our American DNA, our fundamental right to be confusing and illogical.